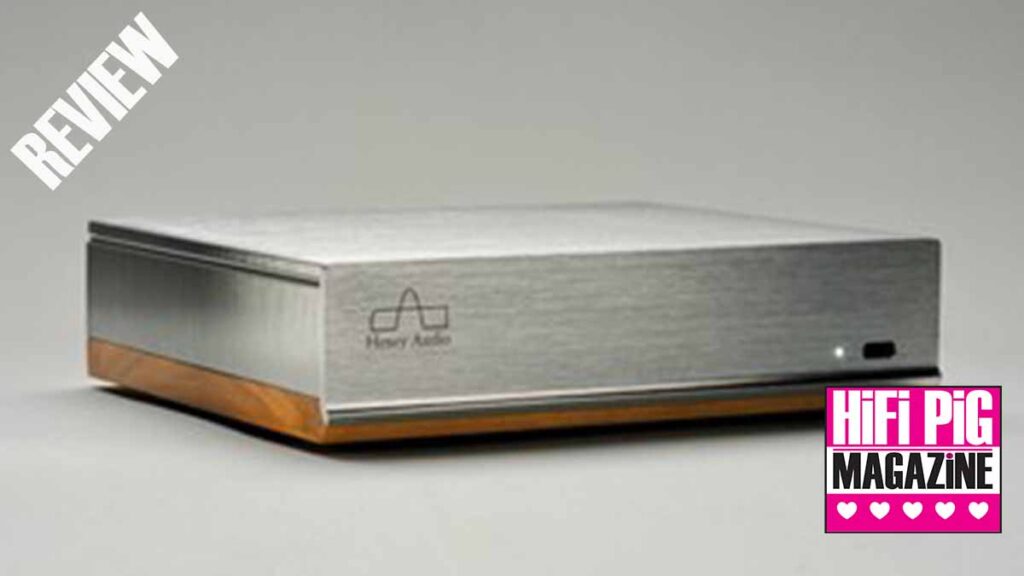

HENRY AUDIO DA 256 DAC REVIEW

Henry Audio DA 256 is born out of 20 years of DIY DAC building; the DA 256 is Børge Strand-Bergesen’s second commercial release. This stylish, compact unit boasts plenty of input options, and the overall design puts a serious focus on making the DAC as simple and easy to use. Jon Lumb takes a look at this DAC costing £1250.

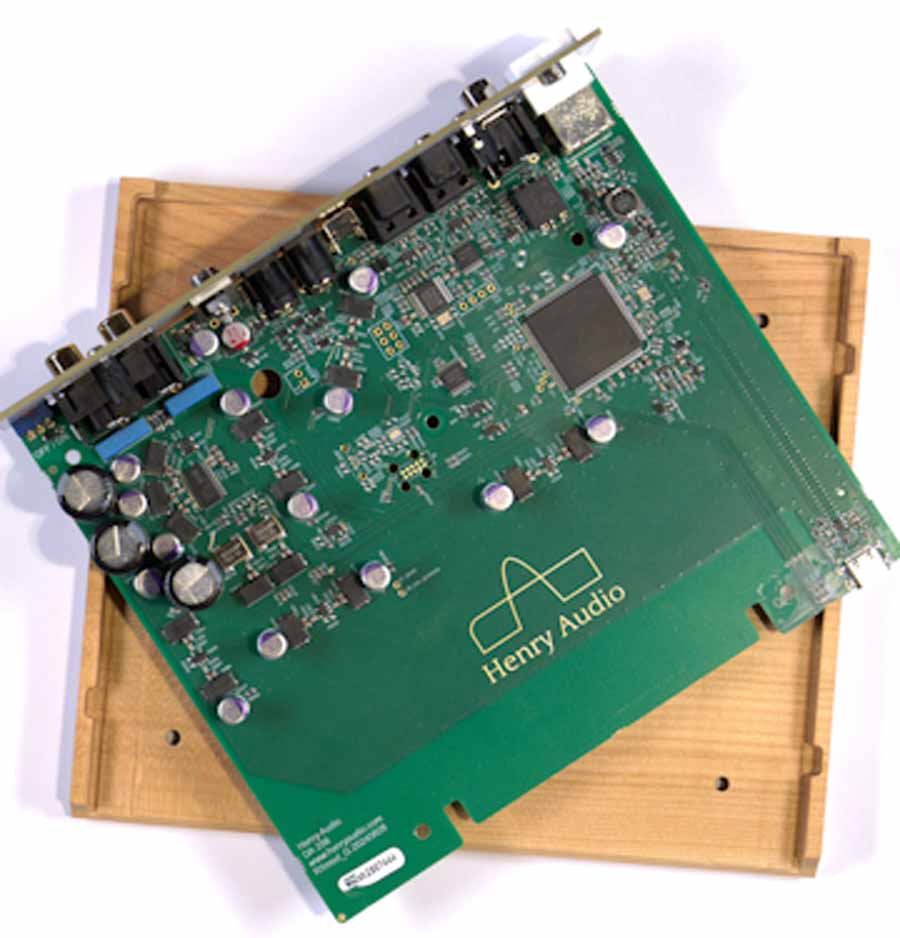

A diehard DIY man, Børge has been building DACs for his own entertainment for 20 years now, which marries perfectly with his career as an electrical engineering consultant. His first foray into a commercial release was the DA 128, which went through 3 iterations. Such was the fan base he managed to build up, he was able to pre-sell sufficient numbers of the DA 256 to fund its full development and initial build costs, which is no small feat. It’s not a conventional approach to funding within the HiFi world (and there have been one or two horror stories over the years of similar schemes vanishing into the aether), but we have the physical product here, so this is definitely not vaporware.

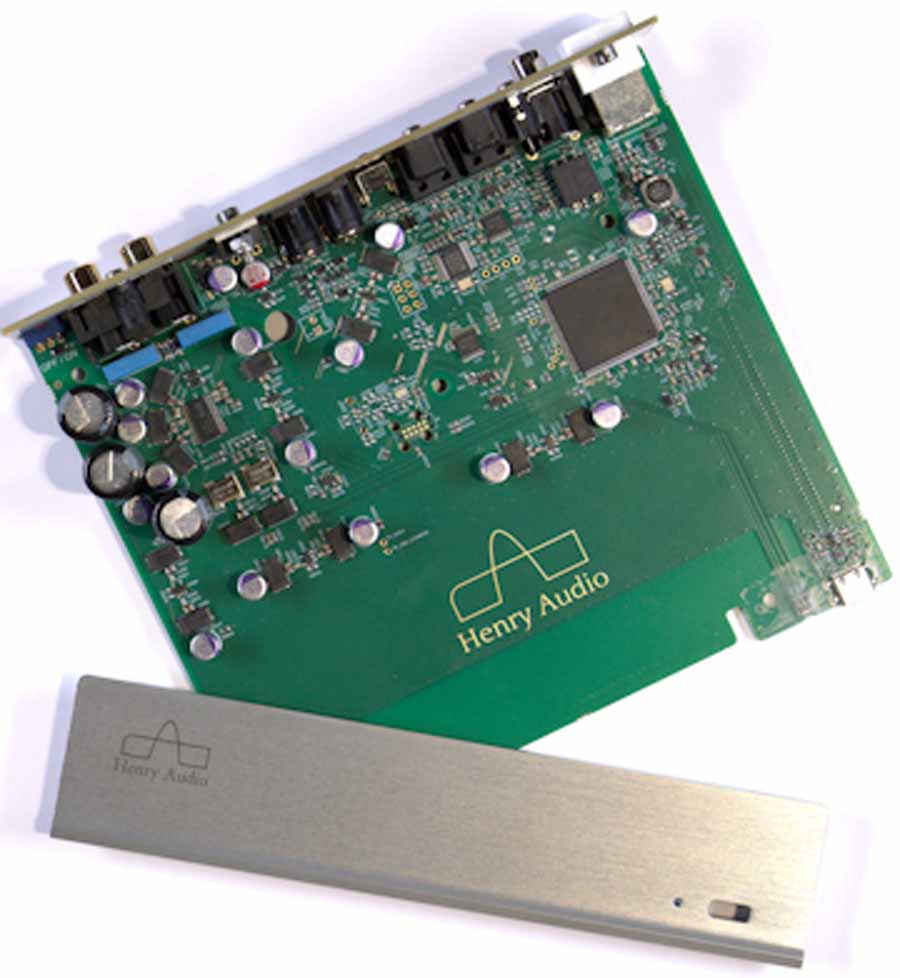

The DIY ethos crops up in a few places; if you’re so inclined, he’s published the full schematic, and you can even get the source code that he’s also written himself. In addition, the DA 256 doesn’t actually ship with a dedicated power supply.

BUILD AND FEATURES OF THE HENRY AUDIO DA 256

There’s a remarkable lack of visible things to comment on here, and that’s in a good way. The DA 256 is doing an awful lot under the hood, but it’s all entirely out of sight, out of mind. It has a standard complement of inputs around the back: USB-B, 2x Toslink, and 1x Coax. In a distinct nod to ease of use, there is also a USB-C port on the front, too. The idea here is that if you have someone else come round and they want to play something, it’s far easier to plug straight into the front of the DAC than fiddling with cables around the back. This front section is connected to the same circuitry as the USB-B port at the back, ensuring no loss of quality.

Notably, there are no options for selecting the source or bitrate anywhere. And this isn’t just one of those scenarios where you can have them via an app or some other software-based connection – you simply don’t get them. Instead, the DA 256 has a scanning program that runs looking for a signal across the various inputs. Once it finds a signal, it automatically switches to that input and automatically works out the data rate it’s working with.

Børge has put a huge amount of effort into making sure the DA 256 sounds good with some truly awful source components. From USB connections from electrically noisy computers, to his encountering sound-cards that gave coax signals that were wildly outside the specification for the interface, the DA 256 has been designed to handle it all. Discrete buffering to help mitigate the effects of any kind of break in the signal is central to this. Most of the software is written in C, which is already bad enough IMHO, but various facets of the USB controller required dipping into Assembly language. If you’re not au fait with programming, C is pretty horrible to work in, but Assembly is generally just horrific. I had the misfortune to have to write some while at university, and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. It’s definitely a testament to the dedication to the product! I was particularly taken with the fact that the processing allows for timing drift from the source component and then uses periods of silence to play catch-up.

SET UP

Unsurprisingly, the majority of the setup is about as simple as these things get. Plug in some cables. Done.

How you power the DAC is the only real decision-making to be done. The easiest way is by the rear USB socket – it can be driven entirely via the power supplied by an attached laptop. On top of that, you have two dedicated power connector options, which will take anything from 8V through to 16V power supplies. Børge’s perspective on this was that lots of people have all manner of existing power supplies, and so he wanted to add flexibility, whilst also not requiring people to purchase an additional power supply they probably didn’t need. I don’t know how many folks actually have spare units floating around in the general populace – I suspect this perspective reflects what the DIY community is like rather than the more general populace at large. If you choose, you can even run it from a simple 9V battery, which is pretty unusual.

There is a dedicated power supply unit in production, which will be pretty much an identical aesthetic match to the DA 256, minus the front USB-C port.

For this review, I ran it using both the USB port on my MacBook Air and a dedicated PSU that was supplied by Henry Audio. To my ears, there was no noticeable difference between these two options – I suspect the laptop sending power from a battery makes it rather cleaner in terms of USB power delivery than if you were running it via a desktop PC.

SOUND QUALITY

I ran into a bit of an issue when I first unpacked the Henry. Because of the ludicrous array of inputs and outputs on my Electrocompaniet (you can literally run a dedicated pre-amp in the middle if you’re really desperate), I’d somehow convinced myself it actually had a digital output from the streamer. It does not. Whilst waiting for a suitable cable to arrive to allow phone/laptop connections, the only digital output I could generate was my old CD player. It’s nothing special at all, and I mostly keep it for the odd occasion when I want to play something that Qobuz no longer has in its library. I decided to lean into the fullness of a Bob Ross “happy little accident” and take a departure from my usual process for assessing a new piece of equipment.

Under ordinary circumstances, I have a Qobuz playlist of tracks that I know extremely well, and I play through that (sometimes, if I’m feeling really wild, I’ll even set it going on shuffle). Based on my initial impressions, I’ll then branch out into other albums as things cross my mind, with a side order of whatever I’m listening to for the fun of it. And after all, whilst I could probably write all my reviews based on that 30-track playlist, you’d all get very bored, very quickly, hearing about the presentation of those same tracks every time you read one of these pieces. So to get the ball rolling, it was a foray into John Martyn, and a live recording made in Bremen, Germany, back in 1986. I’m not going to lie, this was a terrible decision on my part. I adore John Martyn, and the playing on this release is fantastic, but I can only guess they recorded it hot off the desk into a cheap Walkman onto an aging cassette tape. It’s an absolute shocker.

Moving quickly onwards, I stuck on John Grant’s live album recorded with the BBC Philharmonic. John Grant’s a phenomenally versatile artist, and whilst a lot of his studio work has ended up more in the electronica end of the spectrum, he’s an extremely talented pianist and clearly has a great depth of knowledge in the world of classical music. It actually starts with a brief little introduction from John himself, given at the beginning of the concert. I’ve heard tell of people who do almost all of their kit evaluation based on purely spoken word recordings – this strikes me as bonkers, but using some pure spoken word is not without its merits as a real test of the naturalness of the presentation. I’m guessing, but I suspect that as humans have evolved, nuance around the human voice has been something given more priority in the brain than other aspects of audio processing, so it will stand out. Grant’s voice here is everything one would hope for, and more. It comes through the DAC as clear, natural, and with lots of lovely detail to that slightly gravelly quality it has. As It Doesn’t Matter To Him actually kicks in, we’re greeted by quite a rich sound, and there’s quite a bit going on. The Henry gives a great sense of clarity – there’s a risk of the prominence of the bass guitar dominating a bit, but all the other instruments have their place, and the balance is all there. We do perhaps run into a slight issue once the full orchestra is on board, in the form of a touch of brightness between the violins and brass section at the peaks.

I feel I should point out at this point that Henry is dealing with the output of a pretty elderly, low-budget CD player, and it’s then going into my Electrocompaniet, the amp section of which costs about 5 times the price, and onto a set of Piega Coax 411 Gen2 standmounts, at £7,900. While there are more analytical amps than the Electrocompaniet, it’s still pretty transparent, and the ribbon tweeter and mid-range driver in the Piegas is revealing in the extreme. The fact that the Henry holds its own in an environment where any issues are going to be revealed in excruciating detail is really quite seriously impressive.

As we move through to Mars (and another helpful spoken word introduction), the bass guitar is back and volume-wise, quite prominent in the mix, but it’s being played quite high up its range, so there’s not the same energy, and so the dominance is really no longer there. It’s actually quite interesting to hear, because it’s not common to hear them played in that territory, at least outside of jazz fusion territory. You also get really excellent treatment of the drumkit – back in my teens, cymbals in particular would be one of the first things I’d notice sounding off if the bit rate dropped off from CD-quality (and there were a lot of terrible MP3s floating around in those days). Here, they’re wonderfully clear, with that shimmering effect you get from the ongoing vibration of a ride cymbal being really evident. It gets a bit lost in a lot of the track, but there’s also a really lovely acoustic guitar sound that makes its presence felt from time to time. It’s not going to knock Wish You Were Here off its spot of great acoustic guitar recordings, but it fits really well in with all the other instruments, and the Henry really does a great job of making sure that subtlety is conveyed.

I’ve recently come across the concept of recordings that were made using QSound. As I’ve probably mentioned previously, things like stereo image have never been a particularly significant focus for me, but I’m aware they are for a lot of people, so I’ve been digging into all things positional, and so hearing about QSound caught my eye. There doesn’t seem to be a huge number of albums recorded using it, but I did use it as an excuse to revisit Sting’s The Soul Cages.

The imaging here is really quite pronounced – instruments all sit in quite distinct places about the soundstage, and it makes for quite a fascinating experience. I’m very used to a drum kit coming from right in the centre of the soundstage, but it tends to feel like it occupies a fairly uniform space within that. Listening to All This Time, and there’s a much more accurate reflection of precisely where each drum would be on the kit, with the snare and hi-hat coming strongly from the right-hand side, and then the bass drum sits right between the speakers, with the cymbals then dotted all around.

It’s also a remarkably punchy-sounding album; the contrast between the album versions of All This Time and Mad About You vs the live performance on the album All This Time is notable. I find there can be a real risk of listener fatigue with really punchy sound (I can think of at least 2 very well regarded speaker manufacturers I cannot enjoy for more than about 10-15 minutes due to how aggressive the punchiness is), but a full play through of The Soul Cages produced no issues at all here, which can only be considered a good thing.

QUIBBLES

The only real quibble I have with the Henry is the way it communicates the input it’s actually playing, which is via changing the colour of the little LED on the front. This same mechanism is also used if you want to check the bit-rate it’s receiving (which also requires pressing a small button on the rear of the unit to activate this mode – one that’s extremely close to the main Reset button). As all you get is a colour change, this requires looking it up in the manual, which isn’t ideal. I doubt it’s going to be a major issue for many people, not least because source selection is usually pretty obvious based on what’s actually playing, but I’ve included it for completion.

CONCLUSION

The Henry Audio DA 256 is an extremely competent bit of kit. I’m quite impressed with how well thought-out the implementation is, and how much it just does for you. I’m sure there might be a few people with edge cases where the way it does things might be an issue, but I suspect, for the vast majority of people, this is going to be one of the easiest items to set up in their hifi. It needs its cables, and then it just gets out of the way and lets you get back to your music entirely devoid of fuss or any issues of audiophilia nervosa.

It’s also lovely to see such a degree of consideration for user experience – I fully appreciate that for many audio designers, everything is about the pursuit of sound, but there are some wilfully obstreperous user interfaces out there, and fixing them wouldn’t be doing anything to compromise the sound quality of the end product.

AT A GLANCE

Build Quality and Features:

Solid, compact little unit

Plentiful complement of inputs

Sound Quality:

Neutral balance, no emphasis or lack thereof anywhere in the frequency spectrum

Lots of lovely detail, even from

Value For Money:

Absolutely bang on the money here, it’s suitably well made, well equipped, and sounds spot on

We Loved:

The overall sound quality

The real attention to the user experience and ease of use

The way it handles poor-quality transports

We Didn’t Love So Much:

Having to hit a button on the back to confirm what sample rate was being received, which was precariously close to the reset button

Elevator Pitch Review:

This is an excellent value DAC. The sound is balanced and brings plenty of detail. There’s a real focus on making this perhaps the easiest DAC out there to use, and it does so much of the heavy lifting for you

It’s also excellent if circumstance means you’re using it with a transport that’s not top-tier

Jon Lumb

SUPPLIED SPECIFICATION

Inputs:

- SPDIF Coax

- TOSLINK Optical x2

- USB-B rear

- USB-C front

Sampling rates: 16 or 24 bits PCM at 44.1, 48, 88.2, 96, 176.4, 192 kHz.

Dimensions: 173 x 145 x 47 mm

Weight: 1040 g